Visit our Moral Money hub for all the latest ESG news, views and analysis from across the FT

It’s Nobel season again. There is much speculation about whether Donald Trump’s Gaza deal would get him the peace prize he craves (it didn’t).

The economics prize received less attention – but policymakers could benefit from a close study of the winners’ work, as I explain below.

ECONOMY

Nobel Prize winners warn against lobbying big companies

“Growth for growth’s sake is the ideology of the cancer cell,” wrote the essayist and environmentalist Edward Abbey.

The line is popular among those in the green movement who condemn the relentless drive for economic expansion. Only by halting and reversing increases in production and consumption, degrowth advocates argue, can disaster be averted.

On Monday, the Nobel Prize in Economics Committee awarded the prize to three academics who have shed new light on the drivers of economic growth – and whose work includes ideas about how, in return for degrowthers arguments, this could be sustained in the long term, despite environmental limitations.

The work of Joel Mokyr, Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt has also identified a crucial obstacle to these goals: resistance from powerful corporate incumbents whose influence threatens to hold back not only climate action, but also the broader processes of ‘creative destruction’ that have driven modern prosperity.

Lobbying power

Now is a good time to think about this issue, as major companies step up their efforts against green rules in Europe and beyond.

ExxonMobil CEO Darren Woods just went on a media tour to launch a series of attacks on Europe’s green regulations, saying last month that they were “killing the manufacturing sector and frankly stifling economic growth” – part of a much bigger pressure campaign by the oil company. German Chancellor Friedrich Merz said this last week would oppose a complete ban from the EU on the sale of cars with combustion engines from 2035, after heavy lobbying from the country’s automotive sector. If the past COP climate summits can be any guideHundreds of fossil fuel representatives will attend next month’s COP30 in Brazil.

Centuries before the Industrial Revolution, obstruction by vested interests played a crucial role in holding back isolated technological advances that translated into broader economic liftoffs, according to the work of Mokyr, an economic historian at Northwestern University. (He cites examples, including the unfortunate 16th-century inventor of a new type of loom in Danzig, who was secretly drowned on the orders of the city government.)

Aghion and Howitt, meanwhile, explained in detail why large established companies typically have much less incentive to create disruptive innovations than younger, smaller ones. “Companies persist in the areas where they have already established a comparative advantage,” as Aghion put it in a 2021 book he co-authored. “If companies that have gained experience with combustion engines are left to their own choices, they will not spontaneously choose to focus on electric vehicles.”

Clearly, arguments should not be dismissed simply because they come from large corporations. But the work of these economists suggests that by going easy on big, high-emitting companies, governments will be doing a disservice not only to the climate but to national economic dynamics.

Weak trajectory

The economic and political influence of ExxonMobil and the German car lobby reflects a broader trend that has weighed on the growth of the developed world, according to work by Aghion and Howitt. They showed a clear link between growth rates and ‘creative destruction’ – the concept popularized by Joseph Schumpeter in the 1940s, in which superior new business models and technologies displaced old ones.

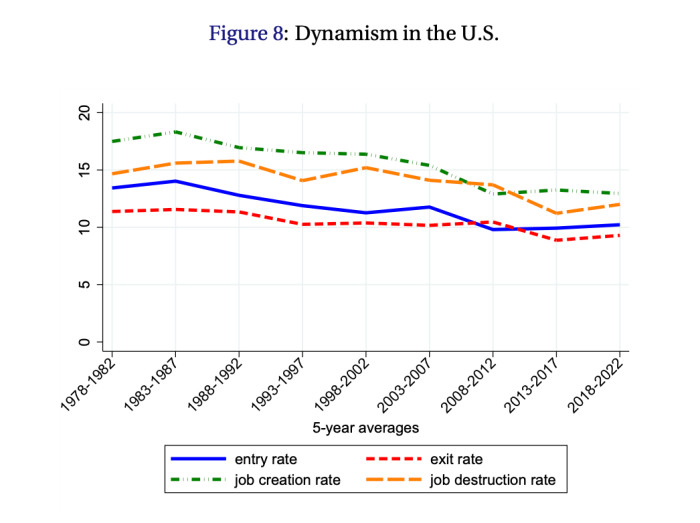

While Schumpeter argued that this process would ultimately lead to the demise of capitalism, Aghion and Howitt claim to have shown that it is sustainable and essential for the long-term flourishing of the system. But as economic power has become more concentrated, indicators of creative destruction – such as the number of business creations and liquidations – have fallen in the US and several other developed countries since the 1980s, along with the average economic growth rate, their work shows. See this diagram from the Nobel Prize Committee’s detailed article on the work of the winners:

Climate change presents a new test for all theories of economic growth. Like other top economists, this year’s Nobel laureates have suggested that historical growth statistics are flattered by their failure to reflect the damage being done to our environment.

To sustain improvements in production and living standards, without undermining the ecological foundations of our economies, government interventions will be needed to support a green form of creative destruction in low-carbon industries, these economists suggest. They point to policies that could shift incentives for companies – whether carbon pricing or financial support for clean technology innovation.

Democracy put to the test

“Economic growth can both save resources and consume resources… the basic idea that per capita income growth must stop because the planet is finite is palpable nonsense.” Mokyr wrote in a 2018 article.

Effective environmental policies, he suggested, are likely to be more effective in democracies than in autocratic regimes, “because concerned public opinions can be better integrated into public policy.” After all, according to Mokyr, a key ingredient of the Industrial Revolution in Britain was the parliamentary system, which played a crucial role in challenging vested economic interests.

China is clearly putting Mokyr’s claim to the test. It is true that coal-fired power stations are still being built at a rapid pace. But it has also used long-term policies and government financing to fuel companies that now dominate entire swaths of the world’s clean energy sector.

And while there are concerns about corruption at various levels of the Chinese state apparatus, Beijing could make a strong case for its policymakers to be less influenced by obstructive corporate lobbying than their Western counterparts. Alibaba’s Jack Ma found out the hard way what can happen to even the largest Chinese companies when they overestimate their policy influence.

Donald Trump has now openly adopted the oil companies’ pro-fossil fuel agenda who have been generous donors to his presidential campaigns. For now, it is up to Europe and the world’s other major democracies to justify Mokyr’s suggestion that they are best placed to lead a global shift towards sustainable growth – and protect the engine of creative destruction from economic actors who fear it.

Smart read

Damage control Consulting firm Glass Lewis will stop issuing single voting positions on shareholder proxy votes, instead offering multiple perspectives to clients. It had been criticized by Republican politicians for its positions on environmental and social issues.

New connections EU officials are seeking to bypass Washington and work directly with US state governments on green issues, a draft policy document has revealed.

Building blocks Can molecular Lego help save the planet?