Unlock the White House Watch newsletter for free

It is all too easy – and all too discouraging – to imagine how future historians might describe 2025 as the year that ended the multilateral vision. For thirty years, the idea of multilateralism as a global public good has flourished. The mind may have flickered at times. But the international agenda is increasingly shaped by meetings devoted to global issues, from climate change to taxes and trade. These summits and their ambitions have all had a disastrous year.

The UN General Assembly, the COP30 climate talks and now, most recently, the Group of 20 leading economies summit all came to a hopeless end. The meager closing statements underlined how quickly and how far the world has retreated from the far-reaching shared vision of about a decade ago for a collective approach to its challenges.

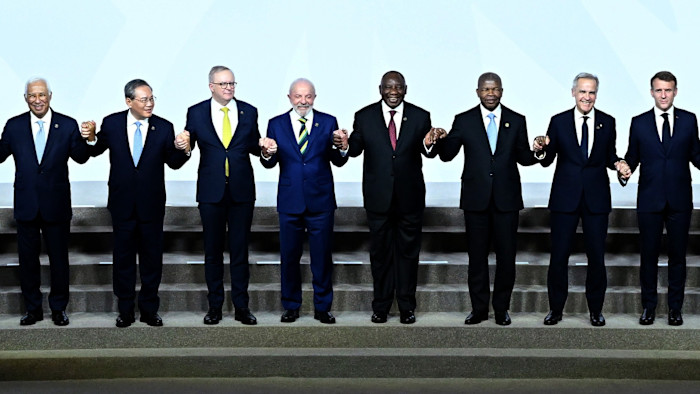

The main driver of this change is US President Donald Trump, with his disdain for the idea that all nations should have a say in how the world is governed – and his disregard for the issues that most need a multilateral global approach, from climate change to free trade. In reality, the world’s largest economy has been hot and cold on multilateralism over the years. But her decision to abandon the case – the Trump administration did not attend the G20 leaders’ summit in South Africa last month – is a hammer blow.

However, it would be unfair to blame the malaise of multilateralism solely on Trump. The cause lost steam even before he started his second term. It never really had a golden age. Other states are happily following America’s example and failing to fulfill their obligations. Then there is the role of China, America’s great power rival. Beijing speaks the language of cooperation, but the country has also followed a mercantilist path and is, for example, complicit in the weakening of the World Trade Organization.

Some of the new groupings of recent years have clearly reached their peak, or are at least redundant for the time being. Take the G20. Previously an unwieldy grouping of disparate powers, the country needed a clear and pressing emergency to galvanize it into joint action: In 2009, during the global financial crisis, the country’s leaders agreed on a massive, coordinated financial injection. In that year, the G20 seemed poised to replace the G8 and declare itself the “main forum for international economic cooperation.” In recent years, it has often struggled to even reach agreement on a final declaration.

The grand old body of multilateralism, the UN, also desperately needs a restart under new leadership. It must sharpen its focus on how to avert the two greatest risks facing humanity today: war between great powers and climate change.

However, true believers in multilateralism must keep the faith. For the time being, they must concentrate on a new, smoother form of collaboration. The buzzword of the day is plurilateralism, the idea of tailor-made gatherings of like-minded countries, sometimes regional, focusing on specific issues. This is the right way. As an example of this flexible spirit, Southeast Asian trade ministers cite the extension of the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership to Britain. The EU is also seeking closer ties.

Such multilateralism is, of course, a pale shadow of the uplifting ambition of some twenty years ago. And in a more contentious world, even this won’t be easy. But there are challenges the world can manage without the US, including trade, development and the biosphere. Also on some of these issues, it is entirely possible that the US will decide over time that it wants to be involved after all.