Southeast Asia has weathered Donald Trump’s tariffs thanks to U.S. demand for technology, cheap production costs and the diversion of goods from China, trade data analysis shows.

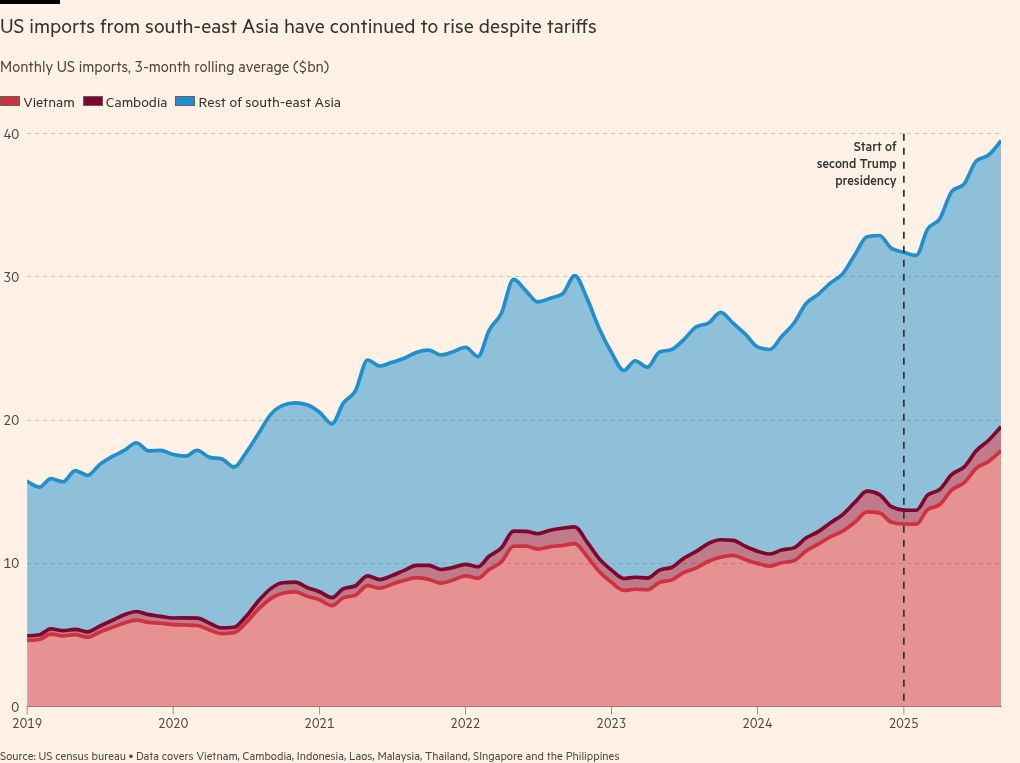

According to data from the US Census Bureau, goods exports from Southeast Asia to the US increased by 25 percent between July and September compared to the same period in 2024, despite the US president’s trade war.

Foreign investment in the region’s key manufacturing economies has also increased, driven by global efforts to diversify supply chains.

The increases defy fears after Trump’s “liberation day” in April that tariffs would hurt the region.

Trump announced “reciprocal” tariffs of up to 49 percent on Southeast Asia’s key manufacturing economies in April, although these were later reduced to around 20 percent through deals with Washington.

“Everyone was worried about reciprocal tariffs at first, but given the cost advantage of producing goods in Asia… a 20 percent tariff is not worth switching,” said Mats Persson, macro and geostrategy leader at consultancy EY.

Even after tariffs, that cost advantage is “somewhere between 20 and more than 100 percent” over making goods in the U.S. or Europe, said Persson, a former adviser to the British Treasury.

This has come as a relief to companies that deployed a “China plus one” strategy during Trump’s first presidential term – using Southeast Asian economies as a second export base to reduce their exposure to the high tariffs imposed on Beijing. These continue to retain water, Persson said.

While Chinese exports to the US fell 40 percent in the third quarter of 2025 from a year earlier, overall Asian exports to the US remained steady, according to US Census Bureau data.

Cambodia, a major manufacturer of shoes and clothing, has continued to grow trade with the US despite the imposition of a 49 percent tariff in April. After negotiations with the White House, this was later reduced to 19 percent.

Clothing is Cambodia’s largest export to the US. Knitwear exports increased by a quarter between the third quarter of 2024 and 2025, according to Trade Data Monitor.

Ken Loo, secretary general of the Cambodian Textile, Clothing, Footwear and Travel Goods Association, said Trump’s tariffs had initially “put pressure” on the sector, but concerns subsided when it emerged competitors in Bangladesh, Vietnam and Indonesia were facing similar obligations.

“The tariffs have not affected anyone. We are at 19 [per cent]. Our competitors are twenty. What’s the difference? . . . If you hit everyone equally, you don’t hit anyone,” he said.

However, Loo added that profit margins across the sector were under pressure as customers asked for discounts to offset the impact of tariffs.

Still, new investments from foreign companies continue to enter Cambodia even with the latest tariffs, with about 90 percent of new investments in Cambodia’s clothing, footwear and travel goods industries coming from companies based in mainland China, he said.

The amount of trade diverted from China — which carries a 37 percent reciprocal tariff — has risen since Trump’s first presidency, reaching a record high of $23.7 billion in September, according to analysis by the consultancy Capital Economics.

As a result, the report estimates that China’s indirect exports to the US are now of a comparable size to direct trade between the two economies.

Cambodia has seen the biggest increase in trade route diversions, with the value of indirect Chinese exports to the US in September up some 73 percent from a year earlier, according to Capital Economics.. There has also been a noticeable increase in trade through Vietnam, Indonesia and Thailand.

Vietnam’s trade surplus with the US reached a record high of $121.6 billion in the first eleven months of 2025, according to official data. Thailand’s imports of raw materials and goods from China rose 34 percent in October, while exports to the US rose 33 percent.

However, analysts warn that Southeast Asian countries face continued uncertainty since the Trump administration vowed to crack down on route diversions through threatening a tariff of 40 percent on all “transhipped” goods. It remains unclear how the US would define such goods.

Southeast Asian countries rely heavily on Chinese raw materials and intermediate goods, and the Trump administration has indicated in talks with countries in the region that it may not tolerate high Chinese content in final products exported to the US.

Another factor behind the region’s resilience so far is the US tech boom, said Leah Fahy, China analyst at Capital Economics. Many technology-related exports, such as chips, chip-making equipment, computers and smartphones, have been exempted from tariffs by the government.

“Electronic goods exports are now growing at around 40 percent year-on-year – faster than at the height of the pandemic – when lockdowns led consumers to binge on electronic products from Asia,” Capital Economics said in a recent note to clients. It predicted that strong demand was “likely to continue” into 2026.

After a recent visit to Vietnam, the region’s top exporter, Tom Miller, an analyst at consultancy Gavekal, said that while foreign investors remained confident the region could weather the trade war, the economy would remain dependent on the whims of the Trump administration.

“It’s still relatively early,” Miller added to customers in December. “[But if the US] moves aggressively to reduce Chinese inputs from global supply chains, Vietnam will be hardest hit: no other country is so integrated into China’s value chain.”