Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

With the friction that President Donald Trump has added to global trade, it appears that shipping companies will face turbulent times. Yet the demand for freight is actually growing. The Danish AP Moller-Maersk expects interest rates to rise by 4 percent this year. Why then do the major shipping companies warn that profitability could be on the rocks?

Maersk, a giant in the maritime transport sector, says it could end up in the red this year for the first time in a decade. Rival ONE recently reported a quarterly loss. The problem is that as demand grows, so does the amount of new cargo capacity coming to sea, and some non-tariff wrinkles in global trade flows are flattening.

Shipping rates rose during the Covid-19 pandemic and were further boosted by geopolitical disruptions such as the closure of Red Sea routes a few years ago, which extended sailing times. Aided by these shifts, executives spent lavishly on new ships.

The problem arises when the need for space on ships decreases, but the capacity does not. By the end of this year, demand for container ships will increase by about 15 to 20 percent over 2019 levels, while capacity will increase by 47 percent, Bernstein analysts estimate. The result is a decrease in freight rates. The Drewry World Container index has fallen 30 percent in the past twelve months, leading analysts to predict an 8 percent drop in Maersk’s annual sales.

While part of the boom and bust cycle is predictable by those at the helm of shipping companies, the world remains subject to disruptions and difficult-to-predict solutions. A smoother process to achieve peace between Israel and Gaza could speed up the reopening of the Red Sea, reducing transportation distances. Conversely, tensions between the US and Iran could easily lead to other problems.

Shippers can communicate these changes in various ways. The industry is now considering ways to reduce costs, such as canceling scheduled sailings, sailing at lower speeds and possibly idling some ships. Scrapping older ships is a last desperate measure.

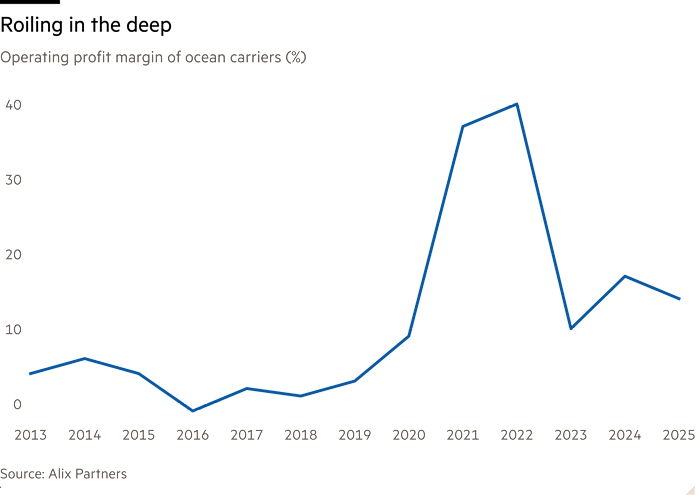

Where they have fortunately learned the lessons of history is in strengthening their balance sheets when times are good. According to AlixPartners analysis, shipping companies’ net debt reached an eye-watering multiple of 7.3 times EBITDA in the years leading up to the pandemic. Since 2020, the ratio has been much more conservative by an average of 1.2 times. Profits in recent years have covered interest payments four to five times.

Maersk underlined the uncertainty when it warned that while it might make a loss this year, it could also – under the right conditions – make an operating profit of $1 billion. That’s a wide range. Shares are hovering around a two-year high, suggesting investors may be too calm about this variability. But they rightly think that the large container lines should remain intact.