Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

The writer is Global Head of Fixed Income at Aviva Investors

For much of modern market history, investors have viewed emerging market bonds as the high-yield, high-risk corner of global fixed income. The logic was simple: emerging economies had volatile politics, fragile institutions and currencies that were prone to sharp devaluations. Developed markets, on the other hand, provided a stable political and policy backdrop.

But the macro and market conditions that once defined “risk” have been reversed, challenging one of the most enduring pricing conventions in global fixed income: the idea that emerging markets should trade at a discount.

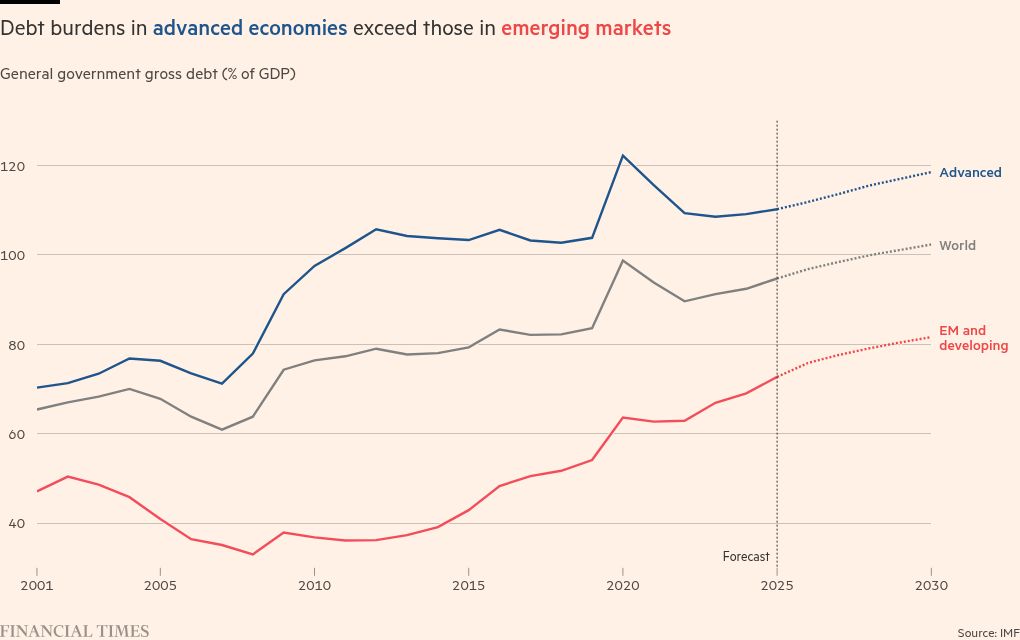

The fiscal position of many advanced economies has deteriorated sharply since the Covid-19 pandemic. The US, which sets the benchmark for global ‘risk-free’ assets in the form of government bonds, now has a budget deficit of over 6 percent of GDP and a debt-to-GDP ratio of almost 120 percent; both levels are typically associated with emerging government bonds that are under pressure. Japan’s ratio exceeds 230 percent, while in Europe the aging population and ongoing spending obligations are increasing the debt burden.

Moreover, geopolitical risk is increasingly concentrated on developed economies. Credit rating agencies are taking notice: Moody’s downgrade of the US credit rating in May and the Scope Ratings downgrade in October, which cited governance and deterioration in fiscal policy, highlight how the line between “safe” and “risky” debt is blurring. Compare that to the evolution of many emerging markets. The fiscal and monetary response to recent global shocks has been much more orthodox than in previous cycles. Central banks in Brazil, Mexico and Chile, for example, raised interest rates around the pandemic, long before the major economies started moving.

Debt statistics are also more favorable. According to IMF data, the median public debt ratio of emerging countries is about 70 percent, compared to 112 percent in advanced economies. Several frontier and middle-income countries, notably Indonesia, India and the Gulf States, have introduced medium-term fiscal frameworks aimed at maintaining debt sustainability while supporting infrastructure and social spending. Institutional progress has also been significant. The introduction of inflation-targeting regimes, deeper local currency bond markets and improved external buffers have now become entrenched norms, reducing historical vulnerability to capital flight crises.

But despite these shifts, emerging market government bonds continue to trade at substantially higher yields than their developed market equivalents. The JPMorgan GBI-EM index of local currency bonds currently yields about 5.92 percent, versus 3.45 percent for the Bloomberg Global Aggregate. That premium is becoming increasingly difficult to justify. Credit quality gaps within the emerging universe have widened, but a growing share of emerging market debt is now well within investment grade.

If investors valued risk based on fundamentals rather than convention, parts of emerging markets would likely earn a valuation premium. Take Mexico, which has a debt-to-GDP ratio of 49 percent, less than half that of the US. Or Indonesia’s 10-year local bond yield, which yields roughly 6 percent despite consistent current account discipline and a young, growing workforce.

Three forces could accelerate this repricing. Firstly, the global savings surplus is now structurally declining. As aging populations in advanced economies begin to take away assets, capital will increasingly flow to regions with higher productivity and demographic growth. EMs fit that description.

Second, the emergence of local investors, namely pension funds, insurers and sovereign wealth funds, anchors demand for domestic debt, reducing dependence on volatile foreign inflows. In India, for example, local institutions now own more than 90 percent of government bonds, making the market more resilient to global shocks.

Third, the inclusion of indexes increases access for global investors. Bloomberg and JPMorgan’s recent inclusion of Indian and Saudi Arabian government bonds in major indices, and other ‘watchlist’ candidates likely to follow, are driving passive inflows of $30 billion to $50 billion into the asset class. More broadly, emerging market debt still accounts for a small portion of most strategic asset allocations. This can only grow.

The world has changed faster than pricing conventions. Bond investors who continue to define “risk-free” as “developed” and “risky” as “emerging” will soon have these assumptions tested by data, demographics and debt dynamics.